Kahu's Mana‘o

Eighth Sunday After Pentecost

Sunday, July 14, 2013

The Rev. Kealahou C. Alika

“Caring Neighbors”

Colossians 1:1-14 & Luke 10:25-37

It has been all over the news over the last several weeks – in newspapers and magazines, on television, radio and the internet. Lawyers in Sanford, Florida including prosecutors and defense attorneys in the trial of George Zimmerman offered their closing arguments at the end of the week.

Florida is one of several states with a “stand-your-ground” law. The law allows for a person to use force in self-defense when there is reasonable belief of an unlawful threat, without an obligation to retreat first.

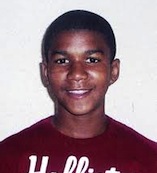

Zimmerman, 29, got into a scuffle with 17-year-old Trayvon Martin after spotting the teenager on a rainy night in February 2012 walking through the Retreat at Twin Lakes, a gated community where he lived. As a neighborhood watch volunteer, Zimmerman claimed that he shot and killed Martin in self-defense. (The Maui News, Friday, July 12, 2013, A5)

Whatever our thoughts and opinions may be about the “stand-your-ground” law and the verdict returned by the Florida jury yesterday, it would be difficult not to consider the ways in which the parable of the Good Samaritan might inform our understanding of what it means to be a good neighbor.

One day a lawyer asks, “What must I do to inherit eternal life?” (Luke10:25) Jesus has the lawyer answer his own question when he asks him, “What is written in the law? What do you read there?” (Luke 10:26)

The lawyer responds “to love . . . God . . . and your neighbor as yourself.” (Luke10:27-28) Jesus encourages him to “do this” – to love his neighbor. (Luke 10:28) Wanting to test Jesus the lawyer asks, “And who is my neighbor?” (Luke 10:29)

It is then that Jesus responds by telling him a parable of a man who was robbed and severely beaten. Several men pass by. Two avoid him. But the third, a Samaritan, stops to lend aid and comfort.

By telling the parable Jesus makes clear that to ask, “Who is my neighbor?” is to ask for a “definition of the object and extent of love.” (Preaching Through the Christian Year, Year C, Craddock, Hayes, Holladay & Tucker, Trinity Press International, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, 1994, page 336) Jesus’ question as to who of three proved himself to be a neighbor “shifts the attention to the kind of person one is to be rather than to those who are or who are not one’s neighbors.” (Op. cit.)

Twice Jesus says do what you know. (Luke 10:28, 37) And what is it that the lawyer is to do: to show love, to show mercy! (Luke 10:37)

In telling the parable, Jesus assumes that those listening to him know about priests, Levites and Samaritans. He assumes that his listeners know that the priest was a designated official who served in the Temple performing ritual functions and conducting sacrificial services; that in belonging to an elite class they were held in high regard. (Harper’s Bible Dictionary, Achtemeier, Harper & Row Publishers, San Francisco, 1971, pages 821-823)

Jesus also assumes that his listeners know that although there was a clear division between the priest and the Levite, both had active roles in the life of the Temple. It is disconcerting that despite their presence in the Temple and their familiarity with the law that both choose to pass on the other side.

But the Samaritan, a descendant of a mixed population occupying the land following the Assyrian conquest in 722 BCE, is the one who stops and shows mercy. Jesus is very aware that his listeners know about the bitter tension between the Samaritans and Jews (John 4:9), yet it is the Samaritan – not the priest or the Levite – who bandages the man’s wounds and provides him with a place to recover.

It is the Samaritan rather than the priest or Levite who proves to be a neighbor to someone in need. There is no doubt that for those listening to the parable for the first time that this was “a shocking turn in the story, shattering their categories of who are and who are not the people of God.” (Preaching Through the Christian Year, Year C, Craddock, Hayes, Holladay & Tucker, Trinity Press International, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, 1994, page 336)

For Luke and the early church and for us today, the parable reminds us that if we are to be the people of God then we are to act in love – a love that draws no boundaries and a love that expects nothing in return. If we are to inherit eternal life; if we are to be the people of God; if we are to love God then we must love our neighbors – others – as we love our selves, we must always show mercy.

To do so is more easily said than done and that was the challenge Jesus placed before the lawyer. “You know what has been written in the law – to love God and to love your neighbor as you love yourself. That is what you must do. That is what we must do.”

* * *

I saw Auntie sitting over by the Bank of Hawaiʻi on Main Street in Wailuku while Kiko and I were out for our morning walk on Friday. We were on our way home on the mauka side of Church Street.

I met Auntie about a year ago on another morning walk. She was and is an ample woman, large in stature, with a commanding presence.

We had a chance to talk. I discovered she was family to someone I knew. She was very gracious and eager to talk almost as though she were holding court. In more recent weeks she had become more and more withdrawn.

When I noticed her in front of the bank I crossed to the makai side of Church Street. I had heard from someone the day before that she was off her medication again and taken to tossing out expletives about how screwed up the world had become.

I realized as I passed by on the other side that the parable of the Good Samaritan and the man who fell among thieves is not just a fanciful story of unsavory characters. It is a story about all of us, about how we struggle to love by showing mercy to others, about how easy it is to walk on the other side. I lifted my hand and waved to Auntie and she waved back with a smile - and that was enough. We are after all neighbors to each other.

* * *

There were two victims that dark and rainy February night in Sanford, Florida over a year ago. Martin and Zimmerman did not know each other. The great sadness of that night is that both young men were overshadowed by mistrust and fear.

Perhaps if they had been able to see that through the shadow of their mistrust and fear of one another and the darkness of that night, they would have shown mercy to each other. The great, great tragedy of that night is that they were in a very real sense – neighbors to each other.