Twenty-second Sunday After Pentecost

Sunday, October 25, 2015

The Rev. Kealahou C. Alika

“Healing and New life”

Job 42:1-6, 10 and Mark 10:46-52

It may be that the story of Job is more familiar to us than the story of Bartimaeus. The Book of Job was written sometime between the 7th and 4th centuries BCE. The author is anonymous though some ascribe the writing of the book, by tradition, to Moses.

There is some debate among Biblical scholars about whether or not Job was a real person, an historical person. Some are convinced that Job was a figure like other figures in the parables of Jesus (Luke 10:30-37; 15:11-32; 12:16-21) and that the story was meant to convey a teaching more than it was to convey a story about the life of an actual person. Others, however, point out that there is mention of Job in other portions of the Bible including comments made by the 6th century prophet Ezekiel. Ezekiel viewed Job as a man of antiquity known for being a righteous man.

There is also some debate among scholars about whether or not Bartimeaus was also a real, historical person. Some contend that he was an historical person given that an actual name is mentioned - Bartimeaus, “Son of Timaeus” (The Gospel According to St. Mark, Vincent Taylor, St. Martin’s Press Inc., 1966, page 448). Others see the story of Bartimaeus as a reference to Plato’s Timaeus and Plato’s own formal written work involving “sight” or the ability to see and perceive “as the foundation of knowledge” (Sowing the Gospel: Mark’s World in Literary-Historical Perspective, Mary Ann Tolbert, Fortress Press, 1996, page 189).

Whatever the case may be there is no debate that the story of Job addresses the theme of God’s justice – or that the story seeks to answer more simply the question that is often asked: “Why do bad things happen to good people.” There is also no debate that the story of the healing of the man born blind that is recorded in The Gospel According to John includes Jesus’ response to the disciples when they asked, “Rabbi, who sinned, this man or his parents, that he was born blind?” (John 9:1-2).

While that question is not asked of Bartimaeus, no doubt that question was in the back of the minds of those who “sternly ordered him to be quiet” as he called out to Jesus the day that Jesus passed by the roadside where he was sitting. When those who were in the crowd sought to silence him, Bartimaeus “cried out even more loudly.” They were probably much like Job’s three friends who were convinced that Job’s suffering was a punishment for his sins (Job 1-22; 11:1-20 & 18:1-21).

Thankfully, Job holds fast to his innocence and Bartimaeus refuses to remain silent. The conclusion of both stories share a common outcome.

There are those who may look upon Job’s final response to God as an act of contrition when he says, “ . . . I despise myself, and repent in dust and ashes” (Job 42:6), as reason enough to look upon Job with disdain. But in his response to God, Job simply declares: “Now my eyes see you” (Job 42:5) and as a consequence of his declaration, God restores his fortunes.

After Jesus calls Bartimaeus to himself and asks him, “What do you want me to do for you?” Bartimaeus answers, “Let me see again” (Mark 10:51). The Bible tells us that immediately Bartimeaus regained his sight and followed Jesus “on the way” (Mark 10:52).

In both instances Job and Bartimaeus have their “sight” restored. We are told that after having his own fortunes restored two-fold, Job lived and died, “old and full of days” (Job 42:17). As for Bartimaeus, we can only imagine his great distress in the days that followed his encounter with Jesus.

Jesus was on his way to the city of Jerusalem. Along the way, he makes the disciples and others aware of his impending death. If he followed Jesus all the way to Jerusalem and beyond, we can assume that Bartimaeus was there to see Jesus’ trial and crucifixion. I imagine that initially Bartimaeus may have found himself wishing that his eyes had not been opened.

Carole Etzler wrote the words and music to a folk song entitled, “Sometimes I Wish,” in 1974. I first heard the song not long after it was written while I was in seminary in California.

It was sung by a classmate who had recently “come out” to his family, letting them know that he was gay. He explained how difficult it was for him and how difficult it was for his family and that from time to time he wondered if it would have been better not to have said anything at all.

Then he heard the song Etzler had written for herself and for other women. Its lyrics are applicable to all who struggle to be free from the fear and hatred of others.

Sometimes I wish my eyes hadn’t been opened.

Sometimes I wish I could no longer see

All of the pain and the hurt and the longing of my

Sisters and me as we try to be free.

Sometimes I wish my eyes hadn’t been opened,

Just for an hour, how sweet it would be

Not to be struggling, not to be striving,

But just sleep securely in our slavery.

But now that I’ve seen with my eyes, I can’t close them,

Because deep inside me somewhere I’d still know

The road that my sisters and I have to travel:

My heart would say, “Yes” and my feet would say “Go!”

Sometimes I wish my eyes hadn’t been opened,

But now that they have, I’m determined to see:

That somehow my sisters and I will be one day

The free people we were meant to be.

(Carol Etzler, Sisters Unlimited, Bridgeport, Vermont, 1974)

Etzler’s struggle is Bartimaeus’ struggle. It is a struggle that speaks to broader truth of how we are all sons and daughters of God; how we are all brothers and sisters to one another.

The Rev. Dr. Allan & Elna Boesak and their daughter Andrea are good and dear friends of our church family. They are from Cape Town, South Africa and currently residing in Indianapolis, Indiana where Allan is serves as the Chair of the Desmond Tutu Center for Peace, Global Justice & Reconciliation at Christian Theological Seminary and Butler University.

Kahu Boesak has preached from this pulpit over the last three summers. We have heard him share his thoughts with us. But it was over shared meals and more informal moments that we learned much more from him and his family about their own Christian journey shaped by their experiences in South Africa.

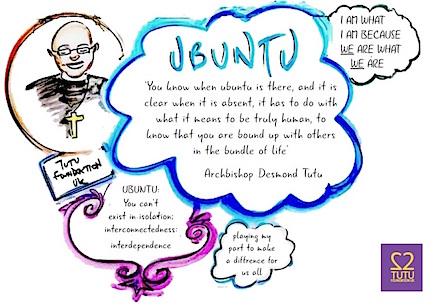

Among the lessons learned is an understanding of ubuntu. Ubuntu is a word that comes from one of the Bantu dialects of Africa. The word, like many of our own Hawaiian words, has its own kaona or meaning that is not always expressed adequately in English.

Within the word itself is the following meaning: There exists a common bond between all of us, no matter how hard we may try to separate ourselves from one another; no matter how much we may seek to separate ourselves from one another by race, gender, class, nationality, religion, physical ability, sexual orientation, marital status and yes, even our political affiliations. It is through the common bond we share - through our interaction with one another - that we discover our own humanity.

Archbishop Desmond Tutu describes ubuntu this way: “It is the essence of being human. It speaks to the fact that my humanity is caught up and is inextricably bound up in yours. I am human because I belong. It speaks about wholeness, it speaks about compassion.”

“A person with ubuntu is welcoming, hospitable, warm and generous, willing to share. Such people are open and available to others, willing to be vulnerable, affirming others, do not feel threatened that others are able and good, for they have a proper self-assurance that comes from knowing that they belong in a greater whole.”

“They know that they are diminished when others are humiliated, diminished when others are oppressed, diminished when others are treated as if they were less than who they are. The quality of ubuntu gives people resilience, enabling them to survive and emerge still human despite all efforts to dehumanize them” (www.tutufoundationuk.org/ubuntu/).

Tutu goes on to say that we cannot exist as human beings in isolation. We are all connected. We cannot be human beings all by ourselves, separated from others.

In some ways Job’s three friends may have sought to set themselves apart from him. And in some ways those who were on the roadside near Bartimaues may have sought to set themselves apart from Bartimaeus. When we recognize Jesus as Bartimaeus did, when we really see and recognize who Jesus is and call out to him, he offers us wholeness and healing, calling us to new life.

May the Spirit of God open our eyes, ears, and hearts to see the face of Jesus Christ in others. As we approach the upcoming season of Advent, may we proclaim once more, “Benedictus qui venit in nomine Domini. Hosanna in excelsis! Blessed is the One who comes in the name of the Lord. Hosanna in the highest!” (Mark 11:9). Amen.