Kahu's Mana‘o

Third Sunday After Pentecost

Sunday, June 9, 2013

The Rev. Kealahou C. Alika

“Healing Love”

1 Kings 17:8-24 & Luke 7:11-17

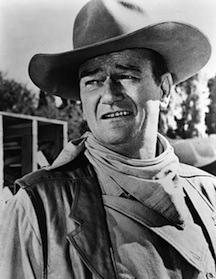

My mother took great pride in calling attention to the photograph of the Hollywood actor John Wayne. She would always have the photograph out in a prominent place wherever we lived for everyone to notice. “See,” she would remind us pointing to the lower corner of the photograph, “he signed it right there.”

We often spent weekends at the Keahou Bay fishing and swimming. We would spend the night at an old beach house that was built on property owned by my tūtū or grandfather. It was on one of those weekends while John Wayne was on vacation that my mother met him and managed to acquire the photograph with his autograph.

We often spent weekends at the Keahou Bay fishing and swimming. We would spend the night at an old beach house that was built on property owned by my tūtū or grandfather. It was on one of those weekends while John Wayne was on vacation that my mother met him and managed to acquire the photograph with his autograph.

By that time he had already become the quintessential icon of American manhood through numerous movies about “cowboys and Indians” that were made in the 1950s. As children we knew about the paniolo or cowboys who worked the ranches in Kona, Waimea and Kaʻu. But we did not know much about Indians except for what we saw in the movies.

In time we would come to learn that Native Americans were misnamed as Indians by European explorers who mistook their landing in North America for the subcontinent of India. We would also come to learn about the oppression of Native Americans during the early period of colonization and the devastating consequences of government policies that were established in the Westward expansion of what we now know as the United States of America.

But as children we only knew what we saw in the movies. We saw no harm in playing “cowboys and Indians.” It seemed everyone wanted to be a cowboy especially when all it took to arm oneself was a hand gesture resembling a gun. The cowboys would be quick to say, “Bang, Bang.”

The Indians would set two hands together to simulate a bow and arrow respond with, “Peww! Peww!” And always the cowboys would declare themselves on the winning side and say, “Ah, you make, die, dead!” to indicate that a bow and arrow stood no chance against a gun.

One could not be more definitive than that – make was the Hawaiian word for “death.” So to say “make, die, dead” was to emphasize that if you were the target of a gun and you were shot, you were as dead as dead could be.

There would be numerous protests. “Not!” “Uh, uh! You miss.” “Your gun junk. Your gun broke.” Following some argument the battle would ensue all over again. Of course at the end of our play all would be well again. No one really died and there would be more battles to fight another day.

Our readings from the Bible this morning are about dying and death. Far from being child’s play, it is about the reality of dying and death and our response to its impact on our lives. The stories of the widows and their sons at Zarephath and at Nain remind us of a parent’s grief over the death of a child, especially of a mother’s grief and pain. It was a grief and pain that was profound for each woman.

In our reading from The First Book of Kings, the widow at Zarephath is faced with a multitude of circumstances beyond her control. Because she did not “belong” to man – a father, a husband or an adult son – she was without resources and forced to fend for herself and her son. As residents of Zarephath they are “foreigners” and Gentiles without status, without power.

A drought in the land only exacerbates their circumstances. Along comes the prophet Elijah who calls on the widow to give him water to drink and bread to eat, aware that she has little to give. But Elijah reassures her that she will have more than enough and that turns out to be the case.

It seems that all is going well until her son becomes seriously ill. At one point “there was no breath left in him.” Elijah issues a protest to God: “Have you also brought tragedy on the widow with whom I lodge, killing her son?” (1 Kings 17:20) In what can only be described as a dramatic scene, we are told Elijah stretches himself over the child three times, prays to God and her son is revived.

In our reading from The Gospel According to Luke, Jesus resuscitates a young man who had died. The child’s mother is also a widow. Like the widow at Zarephath, she is without resources and lives on the edge of society. Like the widow at Zarephath, she is also overcome by grief and pain.

Jesus responds to her in much the same way that Elijah responds to the widow at Zarephath. Elijah cries out to God for compassion. When Jesus sees the widow at Nain, the Bible says “he had compassion on her.” (Luke 7:14)

He touches the open coffin and calls on the young man to rise and the young man who was dead sat up and began to speak. Those who were in the crowd that day begin to glorify God, saying of Jesus, “A great prophet has risen up among us.” (Luke 7:16)

We may be inclined to conclude that the stories about the widows and their sons is about how two prophets – Elijah and Jesus – were able to overcome even death itself. The widows’ sons were both “make, die, dead.” It seems they were as dead as dead could be and yet each was brought back to life, one by Elijah, the other by Jesus.

If that is the case we may be inclined to believe that the miracle of both the stories is how we too can overcome death. But the miracle is temporary. The truth is that in time the widows and their sons will die and leave this earthly life. The truth is in time you and I will also die and leave this earthly life.

Could it be that the miracle of the stories is about how God’s healing love is boundless and that that love is available to everyone – a widow, a foreigner, a child? Could it be that the miracle is about how God’s healing love is available to us when we may feel as though we are beyond God’s love? Could it be that the miracle is about God’s compassion – a compassion that causes Jesus to respond to the widow bereft with grief, “Do not weep” (Luke &:13)?

The Greek word (splagchnizomai) that the writer of Luke chooses suggests that what Jesus felt within himself refers to as “a churning of the entrails or a turning of the womb.” (Reflections on the Lectionary, E. Louise Williams, Christian Century, May 29, 2013, page 21) In Hebrew, we are told that compassion and womb come from the same root word. For both widows and for Elijah and Jesus such compassion knows no bounds.

What is one of the lessons, then, that we might take with us today from our readings? The stories of the widows and their sons reminds us that were are all capable of receiving and sharing God’s love and compassion, not simply in the face of death, but more especially when we are faced with the difficulties we encounter in life. The miracle is that in our grief and pain we are able to share our love and compassion with and for one another.

John Wayne died in 1979. My mother died in 1999.

Let us pray: We give thanks, O God, that you feed us when we are hungry; that you offer us new life in the midst of despair and hopelessness. Beyond our dreams, beyond our plans, beyond our hopes, beyond our imaginings, you are there, eager to share your healing love and compassion with us. May we always be ready to receive your love and compassion and to share your aloha with others. He pule kēia ma ka inoa o Iesū Kristo. Amen.